Net zero is gifting our future to an increasingly dominant China

By Kemi Badenoch

08 September 2024

Every other year, 164 countries meet at the World Trade Organisation to discuss the rules that govern global trade. This year, representing Britain, I made the case for free trade as a force for good to raise global living standards.

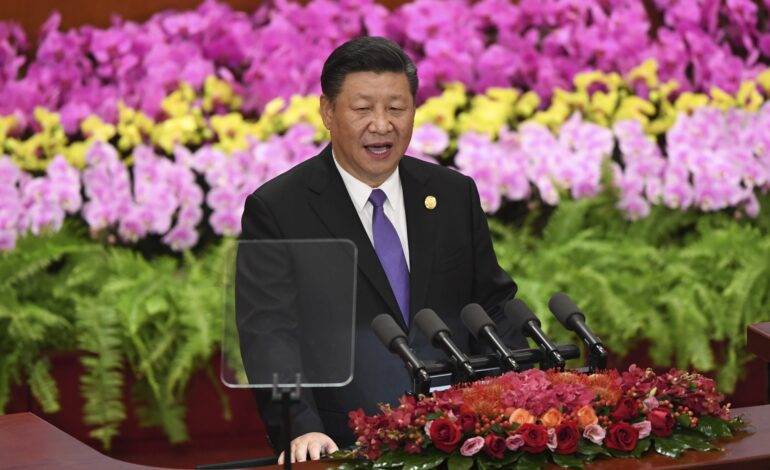

The week saw intense negotiation and plenty of disagreements. They were not between the West and the rest, but between those nations that support free trade and those that do not. However, the behaviour of one country was raised with me by other nations time and time again: China. Trade ministers were candid about the threat China poses to their development. Manufacturing economies fear the oversupply of cheap Chinese goods, particularly those in the automotive industry.

As business secretary, I secured more investment into the British automotive industry in 2023 than in the previous seven years combined. But China has an unusually high number of loss-making firms that receive state subsidy. They are planning production capacity of 70 million electric vehicles by 2030, while global sales of electric vehicles are only estimated at 44 million for that year. Let’s be clear – this is unfair competition. Put simply, China is seeking to flood the market, driving other nations’ industries out of business.

China is enriching itself at the expense of others. It’s not just competitiveness on production cost, it’s also that they don’t play by the rules, stealing intellectual property for technical advantage.

A rare joint statement by the Five Eyes’ intelligence chiefs confirmed this last year. Many countries fear that this economic clout is descending into economic coercion. Last year at the G7 Trade Ministers’ meeting in Japan, I worked with our allies to stop such intimidation. Taiwan is the territory most at risk. Its proximity and economic interdependence to China makes it especially vulnerable. China is even now attempting to intimidate Taiwan with its naval and air assets, trying to put Taiwan on an expensive permanent alert. Furthermore, it is worth reminding ourselves of the brutal clashes China has initiated with ships from the Philippines and Vietnam in pursuit of its illegal seizure of the South China seas. Even if China would like to avoid a costly and violent war to achieve control of Taiwan, economic coercion is an obvious alternative. Taiwan’s allies need to do all they can to support the island’s economy and help it diversify its supply chains. As trade secretary, I strengthened trade ties with Taiwan with an Enhanced Trade Partnership Agreement – the first of its kind between Taiwan and a European country.

Critically for our nation’s future, I also embedded the UK in the wider Indo-Pacific economy by leading the negotiations for the UK to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a free trade bloc worth over £12 trillion and covering 12 countries. CPTPP, with its high standards, will become the leading forum to establish new ways of like-minded allies fighting economic coercion. It is an important part of our future.

In some sense, though, we are all Taiwan. For even if China chose to blockade the island, instead of seizing it by force, the result would lead to a catastrophic collapse in the global economy many, many times greater than what happened as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Sadly, despite the threat China poses, too many of the world’s economies continue to develop a dependency on China, including the UK. This is dangerous for our economy and our freedom. We need to understand exactly how our exposure to China impacts our national security to ensure that we can’t be blackmailed. That could mean an annual statement on trade dependency from the Government, or a National Security Council annual report on dependency. Either way, we need to understand the problem, make it public and find solutions. But we must also mitigate that risk – and that means working to diversify our supply chains so that we become less dependent on China and more interdependent on the rest of the world. Free and fair trade, not global dumping and economic coercion.

Sadly net zero has made dependency worse – and specifically our commitment to meet net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Astonishingly, the decision came without a thorough cost-benefit analysis or any plan to deliver it. We – Parliament – signed up to this legally binding commitment after a 90-minute debate.

China’s production capacity of solar modules is set to exceed global demand by threefold over the next few years compared to what is required to meet the net zero target. Again, it is flooding the market as a deliberate policy. This is a form of economic warfare against the industries of other nations.