Xi takes off the mask: The Beijing tyrant has spent 12 years wrecking China’s image

17 May 2024

By John Schindler

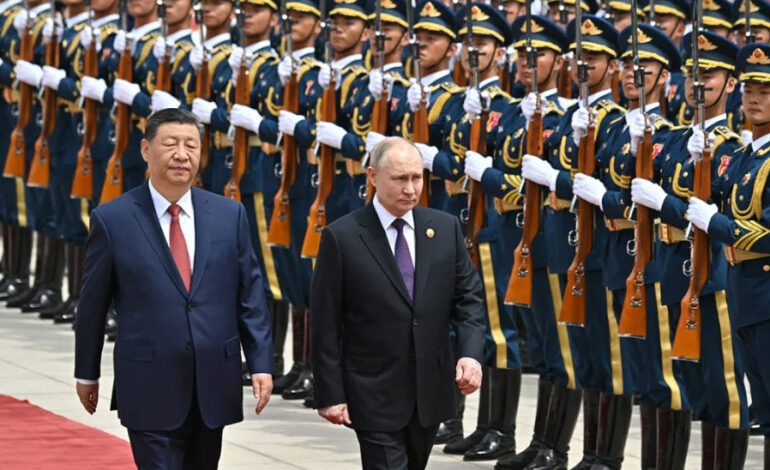

Xi Jinping’s recent European tour was an unprecedented spectacle in international affairs: an Asian leader was arriving as representative of a great power to lesser nations of an anxious continent. China’s strongman landed in Paris on May 5, amid diplomatic pleasantries. Behind the gift exchange, including fine French cognac, any hopes French President Emmanuel Macron harbored that the visit might reverse the deterioration in relations between Beijing and Paris, and the broader European Union, were instantly dashed. Xi cut the figure of an aggressive tough guy. In Paris, he took on the subject of Europe’s most devastating war since 1945, saying, “We oppose using the Ukraine crisis to cast blame, smear a third country, and incite a new Cold War.” He made clear that Beijing’s robust support for Moscow in the third year of Russia’s renewed aggression against Ukraine isn’t something he is willing to compromise or negotiate.

Xi concluded his tour in Hungary, another NATO member, where his reception was far warmer. Upon Xi’s arrival in Budapest on May 8, Xi was given opulent red-carpet treatment by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. Under Orbán, Hungary is seen as an illiberal troublemaker by Western elites, but perhaps because of that, it is warmly embraced by China, which deems it an ideal vehicle for Chinese investments. Xi hailed China’s “deep friendship” with Hungary, the latter’s NATO membership notwithstanding, and the two nations were as one on the subject of strategic cooperation. Orbán expressed his position concisely: “Looking back at the world economy and commerce of 20 years ago, it doesn’t resemble at all what we’re living in today. … Then, we lived in a single-polar world and now we live in a multipolar world order, and one of the main columns of this new world order is China.”

The Chinese Communist Party boss, however, reserved his warmest embrace for Serbia. This was a diplomatic love-in, with Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić offering his Chinese counterpart royal treatment. The capital Belgrade was festooned with Chinese flags, Serbian air force MiG fighters escorted Xi’s plane, and Vučić boasted that his guest, “as the leader of a great power … will be met with respect all over the world, but the reverence and love he encounters in our Serbia will not be found anywhere else.” Warm relations between Beijing and Belgrade are not new, but they have grown cozier in recent years. Chinese investment is a main driver of Serbia’s economy. Vučić explained that “the sky is the limit” when it comes to Chinese-Serbian partnership. For his part, Xi stated China’s position forthrightly: “Eight years ago, Serbia became China’s first comprehensive strategic partner in the Central and Eastern European region, and today, Serbia is the first European country to build a community of destiny with China.”

The anti-NATO and especially anti-American tone of Xi’s Balkan sojourn was deliberate and impossible to miss. Serbia still nurses grievances against the NATO alliance for the 1999 Kosovo War, which included 78 days of NATO bombardment of the Balkan country. Xi’s visit designedly coincided with the 25th anniversary of that war’s most notorious mistake, the U.S. Air Force’s bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade, which killed three Chinese nationals and injured 20 others. Beijing has never accepted the Pentagon’s assertion that this was a terrible mistake, a targeting error. (I was involved in the Kosovo War as a senior intelligence official, and I saw no evidence that the incident was due to anything other than the fog of war.) Chinese emotions over the 1999 embassy bombing remain tangible. “The Chinese people value peace but will never allow historical tragedies to happen again,” Xi told his Serbian hosts. “The friendship forged in blood between the peoples of China and Serbia has become the common memory of the two peoples and will inspire both sides to move forward together.” In short, he implied that China and Serbia were illegally attacked by NATO and the United States, and Xi wanted to make sure both his friends and his enemy across the Atlantic got the message that it would never happen again.

Serbia is an all-purpose Chinese client state in Europe surrounded by NATO members. What is really significant is the boast of Chinese economic and political power, even by a NATO member such as Hungary (and France, less ebulliently). The unipolar world dominated by the U.S. that emerged with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, grounded in American military and economic might, hasn’t merely faded away. It is the subject of deliberate efforts by Xi to displace it. It is the target of his entire worldview and his view of himself as the Chinese leader of destiny whose historical role is to build his nation to global preeminence at the expense of the U.S. and all it stands for.

The collapse of unchallenged U.S. global leadership, after years of slow decline, was made plain by the humiliating debacle of America’s shambolic retreat from Kabul in August 2021. That strategic coda to two decades of diffident and failing American war-making in Afghanistan signaled to the world the incompetence of U.S. diplomacy and military power. Behind a brave face, Uncle Sam was revealed as weary and inept. The Biden administration’s flagrant lies about our Kabul defeat, which the president and his minions continue to peddle even now, have done nothing to counter foreign perceptions. The U.S. under President Joe Biden is seen as a declining superpower in denial. It’s not a coincidence that, just four months after our retreat from Afghanistan, Russian President Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine, judging that America would not fight for Kyiv.

Since the debacle of Kabul, China has been notably more willing to risk confrontations with the U.S. and its military. Clashes between Chinese fighters and unarmed American and allied surveillance planes have grown more frequent and dangerous. The Chinese confront allied warships, particularly in waters close to China. Beijing under Xi is not just willing but keen to take positions and actions that put it at odds with Washington. It is constantly probing and testing, increasingly confident that Biden will blink. Washington begged for months to restore the Pentagon’s hotline to Chinese military leaders in Beijing, which the People’s Liberation Army stopped answering in 2021. Xi agreed to restart it only after Biden made a personal appeal, a modern equivalent of the ancient kowtow, to China’s leader in 2023.

Much though the Biden administration has mishandled relations with China, it must be acknowledged that Chinese belligerence dates back through previous administrations, right back, in fact, to Xi’s emergence as Chinese leader in 2012. He was a new kind of leader, much more aggressive, much more assertive of China’s imperial destiny, much more ready to undermine the impression that China wanted to join the comity of nations. For three decades, America’s political and economic elites, and those of the West generally, believed that Beijing was on a path of democratization and normalization, wanting to be a partner with the West on most issues. Pundits referred to “Chimerica” as a financial partnership grounded in mutual dependency, displacing great power competition. Mutual interest was seen as undergirding good behavior by Beijing.

That was part of the reason China was granted most-favored-nation trading status in 1993, an enormous win for Beijing and critically important to China’s economic rise, early in the first term of President Bill Clinton. China’s MFN status was made permanent in 2001, early in the presidency of George W. Bush. For three decades, few in Washington of either party expressed doubts about the wisdom of assisting China in its rise to global power. Those who raised questions about whether the communist regime was really a long-term partner were in the minority no matter who was in the White House.

Whatever was plausible or otherwise before the arrival of Xi, however, it is now clear that China, under a leader more dominant than any since Mao Zedong, is a great power with aggressive ambitions and little concern for international comity, except insofar as it is temporarily useful in pursuit of long-term Chinese dominance. Xi has initiated and is pursuing a military buildup to match China’s economic achievements, including a blue-water navy to challenge America’s Pacific supremacy. Xi has his own ideas about how the world ought to work, and it’s not how Davos or Foggy Bottom likes it. Although the great man theory of history is out of favor in the West, sometimes a single leader can change the world. Comrade Xi has, unquestionably for the worse, done that.

Since becoming Chinese Communist Party boss in 2012, Xi has led his country onto a path of confrontation, not cooperation, with the West, especially the U.S. The son of a CCP functionary who rose methodically through the party’s ranks, through thick and thin, Xi has not shied away from confrontation, even though Beijing has demurred from open warfare against the West so far, preferring more deniable methods such as espionage, mass-hacking, and political influence operations.

The contrast with Putin is significant. The Kremlin boss took power a quarter of a century ago, and Putin, who is just a few months older than Xi, just celebrated his fifth presidential inauguration. He is Russia’s czar-for-life. Nevertheless, the early years of Putin’s rule witnessed some cooperation with the West. Early on, Putin even toyed with Russia joining NATO. Putin’s hostility toward the West maturated gradually, driven by events, and only became obvious by 2008, with Moscow’s brazen invasion of Georgia. The West never had any such honeymoon with Xi, who possesses the congenital anti-Western views of many CCP higher-ups.

Above all, Xi is a party man through and through, and his tenure as the boss has featured CCP consolidation of rule. Party authority has tightened under Xi, and internal dissent isn’t tolerated much more than it was under Mao, the tyrannical founder of the People’s Republic of China. Xi frequently compares himself to Mao and, like his predecessor, encourages a party cult of personality. Commemoration of the CCP’s 100th anniversary in 2021 featured comparisons between Mao and Xi, flattering to both, while the latter has depicted himself as the party’s most important “helmsman” since Mao. Xi is not “Mao 2.0,” for he has made China a great power. There’s a saying in China that Mao achieved jianguo (establishing the new Chinese republic), Deng Xiaoping, who ruled from 1978 to 1989, achieved fuguo (enriching China), and Xi has executed qiangguo (strengthening China). It is Xi who has transformed the dragon into a global menace.

Xi’s words and deeds make it plain that his aim is global hegemony, with China replacing America in setting the international order. Behind CCP platitudes about China’s “dream of national rejuvenation” by the middle of this century lurks the reality of tianxia (all under heaven), a Sinocentric throwback to China’s ancient past, with the “Middle Kingdom” at the center of global power surrounded by vassals and client states. Xi embraces this archaic ideology as a replacement for the “rules-based international order.” He has stated tianxia as his goal many times. In 2017, he cited it as a “common destiny for mankind.”

Like Putin’s pseudo-historical fantasies about “Holy Rus,” Xi’s ramblings about tianxia are for domestic consumption. But he is saying what he believes. America’s “Manifest Destiny” is two centuries old. China’s asserted destiny reaches back millennia. Xi rejects partnership with the West, which he sees as decadent and in an advanced state of collapse. He wants China to reestablish its place “under heaven,” overseeing a new world order where authoritarian regimes are the norm and Beijing gets the respect — and unchallenged rule over much of Asia, which China sees as its geographic and ancestral right.

It’s difficult to overstate the magnitude of the Chinese spy offensive that Xi has put in place against the West. It is engaged in a full-spectrum clandestine assault that FBI Director Christopher Wray in 2020 declared was “the greatest long-term threat” to America’s future, dwarfing all other security concerns. “The FBI is now opening a new China-related counterintelligence case every 10 hours,” Wray explained, adding that “of the nearly 5,000 active counterintelligence cases currently underway across the country, almost half are related to China.”

Few in Washington’s secret corridors of power doubt that an increasingly aggressive China will act in the second half of this decade in ways that run the serious risk of all-out war. Xi has perhaps a decade of rule left in him before age takes its toll. The clock is ticking, and Xi’s desire to reunite Taiwan with the mainland is not in doubt.

In his dozen years in nearly complete control of China, Xi has exploded all illusions that the most populous nation on Earth, and its second biggest economy, can be regarded as any kind of partner for the future. He has allied himself with the world’s pariahs, including Russia, Iran, and North Korea, and some of its lesser nuisances and has detached itself from rule-of-law liberal democracies, which it now confronts. It has emerged as a threat comparable to or greater than was posed by the Soviet Union in the Cold War. It is as implacable an enemy of our nation and values, and it is increasingly well armed. It also has much more ability to seduce the West, for it is the supplier of goods that ordinary people want. The Soviet Union had nothing but strength on its side. China under Xi has strength and subtlety — and inducements to nations everywhere to prefer its patronage over America’s. Xi is responsible for this. He would like to get all the credit. He should certainly get the blame.