Innovating Repression: Policy Experimentation and the Evolution of Beijing’s Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang

By Adrian Zenz

30 January 2024

This article argues that Beijing’s campaign of mass internment in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region evolved through a creative local policy experimentation process. This resulted in an ‘innovative repression’ solution to widespread ethnic discontent in the region, which the party-state has framed as ‘religious extremism’ and portrayed as a major national security threat. Amid significant top-level steering by the central government and despite extreme political sensitivities surrounding Xinjiang, Beijing used a form of ‘policy experimentation under hierarchy’ to catalyze localized development of mass ‘de-extremification’ in dedicated re-education internment camps. While scholars disagree to what extent policy experimentation continues under Xi Jinping’s more centralized approach to governance, the state’s atrocities in Xinjiang indicate how policy experimentation continues to facilitate the development of next-generation repressive securitization strategies.

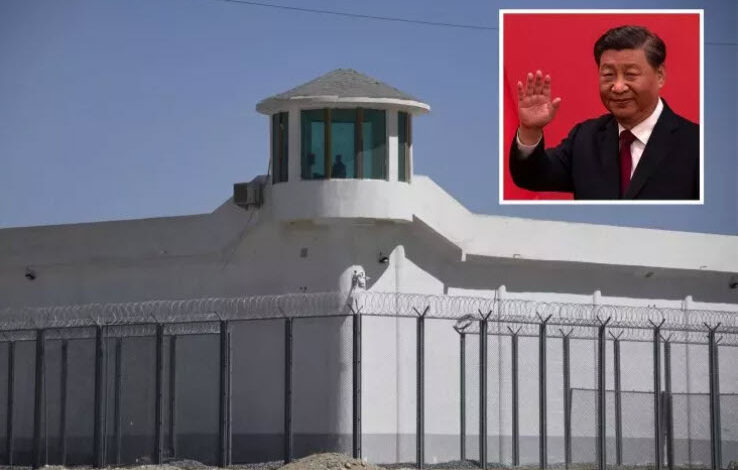

From early 2017, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) embarked on a campaign of extrajudicially interning Uyghurs and other members of predominantly Turkic ethnic groups into re-education camps. Initially carrying a range of designations, such as ‘concentrated transformation-through-education centers’, the state gradually unified their terminology to the euphemistic ‘Vocational Education and Training Centers’ (职业技能教育培训中心) or VSETCs.Footnote1 The author has estimated that up to 1–2 million ethnic group members were interned.Footnote2

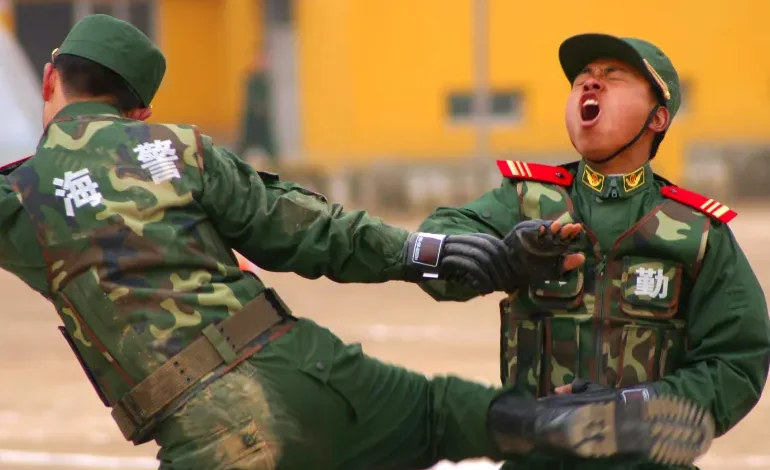

This campaign had been preceded by decades-long tensions between Uyghurs and China’s Han majority population, which in July 2009 erupted into violent clashes in the region’s capital of Urumqi.Footnote3 After a suicide car bombing in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square (October 2013), a train station stabbing in Kunming (March 2014) and a market bombing in Urumqi by Uyghur militants during Xi Jinping’s visit (April 2014), Beijing responded with intensified securitization measures. Under Chen Quanguo, Xinjiang became one of the world’s most heavily fortified police states.Footnote4 After the party-state embarked on a campaign of mass extrajudicial internment, witness accounts, state documents and satellite images have documented the prison-like nature of the VSETCs.Footnote5 In December 2019, the XUAR government announced that VSETC ‘students’ had ‘all graduated’.Footnote6 Many detainees have since been sentenced to seemingly ‘legal’ but effectively arbitrary prison terms, or shifted into forms of forced labor.Footnote7

Scholarship on PRC policymaking has argued that Beijing’s economic reforms and authoritarian resilience, especially during the reform period, derive from its innovative experimental policymaking approach.Footnote8 Scholars disagree about how much policy experimentation continues under General Secretary Xi Jinping’s more centralized approach to governance. While some suggest that under Xi, policy experimentation has declined noticeably and local level innovation is being disincentivized, others argue that centrally controlled policy experimentation has continued ‘under pressure’ as local officials are forced to experiment.Footnote9

Based on important new evidence, this article argues that Xinjiang’s re-education campaign between 2013 and 2019 evolved through a centrally steered yet locally conducted policy experimentation process that closely tracked general patterns of PRC policy experimentation, with implications for wider debates on policy experimentation in the Xi era. In addition to performing mass re-education, the VSETCs also functioned as temporary filtration camps, sorting non-Han populations and ‘releasing’ those considered less problematic into forced labor while sentencing others (especially intellectual and business elites) to long prison terms.

The evolution of Xinjiang’s re-education campaign from a policy perspective remains undertheorized. Scholars have examined the evolution of the XUAR’s ‘ideational governance’ and counterterrorism strategies in the 2010sFootnote10; potential PRC precursors for Xinjiang’s camps and their more immediate policy contextFootnote11; the development of VSETCs’ administrative and security featuresFootnote12; and the potential motivations of Xinjiang’s and Beijing’s leadership with the campaign.Footnote13 Due to his crucial role in overseeing the implementation of the campaign, Xinjiang’s party secretary Chen Quanguo (2016–2021) is frequently considered its mastermind or ‘architect’.Footnote14 In 2020, the author challenged this perception, arguing that Chen was likely brought in to implement a mass internment policy largely developed under Xinjiang’s previous party secretary, Zhang Chunxian.Footnote15 The author further suggested that VSETC-linked forced work placements constitute a significant policy innovation, incorporating proposals to address shortcomings of China’s Re-Education Through Labor (RETL) system advanced by Chinese academics and RETL administrators in the 2000s.Footnote16

Building on prior scholarship, this article argues that the mass internment campaign from 2017 was developed through policy experimentation, combining innovative local piloting with significant central government oversight. This may (1) indicate that policy innovation and experimentation under Xi continue at higher levels than suggested by part of the current scholarship and (2) demonstrate how policy experimentation can undergird forms of ‘innovative repression’ that enable a next generation of targeted human rights violations, achieving regime security at all costs. As such, the article seeks to fill an important gap in the literature on Chinese policy experimentation, which has been largely restricted to analyzing the evolution of economic and social policies.Footnote17

The article proceeds as follows. After discussing methods, it reviews debates on policy experimentation under Xi. It then traces the evolution of the re-education campaign, beginning with Xinjiang’s experimental ‘deradicalization’ or ‘de-extremification’ approaches (in 2013), the role of Xi’s Xinjiang visit (2014) and the development of multi-tiered centralized re-education (2014–15), culminating in the campaign of mass internment from 2017. The article then analyzes local–central interaction as the campaign progressed from experimentation to formalization and finally the enactment of legislation.